On Ambiguity in Art

An ingredient for greater richness and engagement

Yesterday, my wife and I watched a documentary by the production group, “Exhibition On Screen” about the 17th century Dutch artist Johannes Vermeer. You can watch it here on Kanopy. (It’s wonderfully done -- highly recommended. And they have many more on other artists.) Some of the discussion centered on ambiguity in the painter’s storytelling, which enriches the painting for the viewer as much as does the artist’s tremendous skill in the use of light and color. In this essay, I would like to unpack the ways I think ambiguity in all the arts is enriching and engaging by looking at a number of examples.

Let’s look at just one Vermeer to start, The Love Letter:

The expressions of the two women alone provide a myriad of possibilities in understanding this piece. The recipient of the letter appears highly anxious. About what? The maid who has just handed it to her is smiling slightly. About what? What, other than mistress and servant, characterizes their relationship? What symbolic information is conveyed by the paintings behind them, and by other objects in the scene? I find paintings that leave such things up in the air to be far more engaging than those that lay everything out clearly, even when the latter might be done beautifully. And, isn’t that the point?

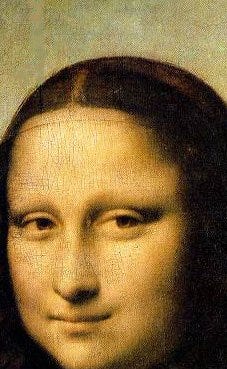

Why is da Vinci’s The Mona Lisa the most famous painting in the world? The answer surely is its inherent ambiguity. What is her smile about? There appears to be a tinge of sadness in it, too. How to reconcile these emotions? It’s interesting to note that the artist used a technique called sfumato, in which subtle transitions between colors and tones create a hazy effect. You can see it in the corners of her mouth and eyes, which are known to be the key areas of facial expression.

It seems clear to me that one of the chief benefits of ambiguity in painting (the same holds for literature, which we will discuss in a moment) is that it forces a closer engagement of the viewer with the work. Humans are naturally curious, and just as we fill in incomplete pictures with ideas of our own, we want a completed story. We also like puzzles. We enjoy considering various possibilities that the artist is communicating. It’s gripping. Moreover, in the hands of an expert, these alternative possibilities speak to and reinforce one another. I’ll illustrate with two of my favorite examples, both from Shakespeare.

Ambiguity has long been recognized as one of the hallmarks of Shakespeare’s genius. So, I am breaking no new ground here. I am merely looking to this element of his genius to illustrate the point that ambiguity enriches and deepens our understanding and overall relationship with the work, especially when the alternative interpretations are related to one another, rather than being simply different.

In the famous deposition scene in Richard II, when Henry asks Richard directly whether he is ready to hand over the crown, the latter responds hesitatingly, “Aye…no…no…aye,” as one imagines (and a good director should instruct the actor to do) Richard putting forward his crown, then withdrawing it as he says “no,” etc. This is a clear surface understanding of these four words. Recalling, though, that theater-goers in Shakespeare’s time were called “auditors” who were highly attuned to listening (whereas in our movie-going age, we are more attuned to seeing), employing the homonyms of words for alternative meanings could be a powerful device. Another way of hearing these words is: “I… know… no… I.” The deeper meaning here is that Richard identifies so strongly with the crown -- recall that he was a child when he came to it -- that he cannot conceive of himself apart from it. Indeed, the rest of his role in the play is largely involved with Richard’s wrestling with his own identity as a deposed king. We will never know with certainty what Shakespeare intended -- and I must caution that this endeavor of looking for and seeing ambiguity carries with it the possibility that we are simply wrong about the writer's conscious intention-- I find it impossible to think that Shakespeare did not intend for these two alternatives to be hanging in the air as the actor spoke them. But that’s just me.

Moving to another favorite illustration of ambiguity from Shakespeare (there are thousands -- and not merely in word interpretation, but also in how to understand the plot), I look to Hamlet (perhaps the best example of enrichment through plot ambiguity, which I won’t discuss here). Already in the first line of his first soliloquy, we have a famous and delicious example of ambiguity: “Oh that this too, too [solid, sullied, sallied] flesh would melt…” The three bracketed words are all alternatives, and highly respected editors have selected different ones. (I find it interesting that word ambiguity, as illustrated by these two examples, is more problematic to capture in the printed play than in the heard one, since a definitive choice must be made in the former, though annotations do ameliorate this.) In fact, the folio editors chose “solid”, while the first quarto had “sallied.” Taking into account that “sallied” may have been an alternative spelling of “sullied,” we have a confusing situation all around. But my point is that confusion is our friend, and we should embrace it.

“Solid” fits best with “melt,” naturally. “Sullied” -- to soil, or make dirty -- certainly, in my view, has resonance with Hamlet’s feelings about his circumstance. Finally, “sallied” -- to be attacked -- also has resonance. (It’s not entirely clear whether “sallied” and “sullied” were different words with the meaning above, or just variant spellings.) I recently watched a video about which word is “correct,” and have read much about it, and find it rather humorous that the two video presenters and all I have read on the issue were solely preoccupied with deciding which word is correct. This misses the entire point. Shakespeare, who used -- by far -- more words than any other known writer in English (inventing many, as well), was, without doubt, aware of all these definitions and the resonances they offered. Therefore, I cannot believe that Shakespeare, who loved punning and other wordplay, as well as ambiguity, didn’t deliberately intend for the auditor to resonate with both (or all three) meanings. And just a little reflection shows how this ambiguity of meaning deepens our understanding of the passage, and most importantly, of Hamlet’s character.

Ambiguity in music is, I think, a little more subtle than in painting and literature. In my recent songwriting, I have been exploring harmonic ambiguity, meaning that it’s not entirely clear what key (or mode) the song is in (though I am not compositionally sophisticated enough to make this strongly ambiguous). A simple example of harmonic ambiguity might be where a C major chord can be associated with different modes, such as C major, G major, and F major. There can also be tonal and metrical ambiguity in music. One example I can point to of harmonic ambiguity is Franz Liszt’s masterpiece, his piano sonata in B-minor. This piece moves fluidly through a number of keys and modes, several times blurring the lines as it transitions from one to the other. Staying with Liszt, he invented the “tone poem,” which is decidedly “programmatic,” meaning simply that there is an intentional idea associated with the music -- a “story,” if you will. Just as the plot of a Shakespeare play, or of a novel, short story, or poem, can incorporate ambiguities, so too can a piece of programmatic music. You may hear, as many do, the Faust story in the B-minor sonata, but I (among others) do not. This ambiguity is enriching because it leads us to hearing the music from different perspectives, rather than just a single one.

I hope that I have been convincing in promoting the importance of ambiguity in all art. The last thing I’d like to say about it is that, as far as I am aware -- and I may well be mistaken -- we live in a time when ambiguity in art seems to be out of fashion. My general experience with visual art, music, and literature of, say, the past hundred years has been that they do not tend to incorporate it (I have no doubt there are exceptions; I’m speaking in generality here), and tend toward a more plain-speaking style. I regret this, since I feel those artists who don’t employ it lose a unique opportunity for greater richness in meaning and engagement with their viewers, listeners, and readers. I myself have tried to incorporate ambiguity in my song lyrics (and increasingly in my music), though I will say, with a laugh -- and perhaps with some deeper meaning attached -- that my best ambiguous outcomes have been “accidental” -- that is, I only became aware of other meanings and interpretations later. The unknown depths and workings of one’s own mind!